Cultures Commune in Crow Country

Part 2: Sitting Bull prepares to bring over 100 families to Crow Country

With the Cheyennes victory over the soldiers at the Battle of the Greasy Grass, the 2 Sioux chiefs led their people north into Canada. Crazy Horse however, would surrender first and be killed in Nebraska one year later in 1877, while Sitting Bull ventured to Woody Mountain, Saskatchewan.

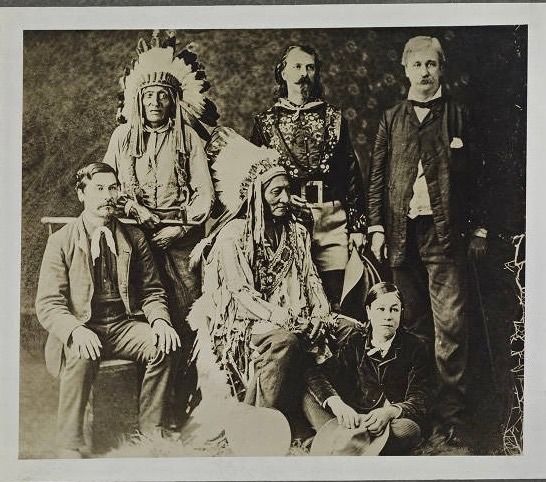

After holding out for four years in the Canadian mountains, Sitting Bull and 186 of his followers surrendered in 1881, while some remained and married into the neighboring bands of Cree, Assiniboine and Blackfeet. Sitting Bull and his faction, after their surrender at Standing Rock Agency, would then be sent to Fort Randall and held as prisoners until 1884, when the Army had decided to return Sitting Bull back to the reservation. The Chief then decided to join the Wild West Show and journeyed to cities like London, Paris and Frankfurt for some time, returning back to the reservation in 1885.

Anthropologist Richard Hoxie said of the Sioux chief, “he thumbed his nose at the government by greeting socialites in the company of Buffalo Bill” and had a somewhat “officious air” about himself.

According to Josephine Waggoner, a witness to the Sioux chief’s time at the Standing Rock agency, Sitting Bull had received an invitation from the Crows to come and visit them the following season during a social dance in 1885. The Crow, who had made plans to gift horses to Sitting Bull’s people, invited their former adversaries to come and stay with them for a visit and to trade, as the Crows had now amassed one of the largest horse herds on the newly formed reservations.

Waggoner said Sitting Bull received the invitation at a large dance and according to an eye witness at the Standing Rock Agency “many people had heard of what was to take place.” The chief had reportedly made plans to set out for the Crow Reservation in July 1886, so that the visit could take place in September.

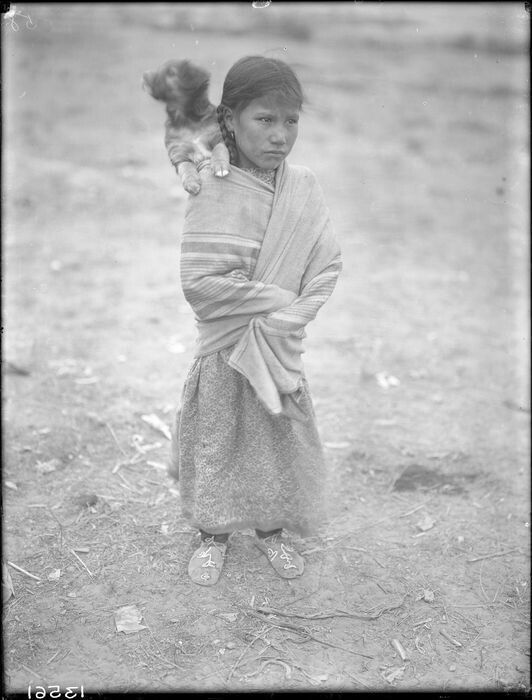

The Crow also were hosting their western allies, the Nez Perce, who Crazy Horse had been asked to scout against in 1877. The relationship between the Crow and the Nez Perce was strengthened when the Nez Perce, fleeing persecution from the soldiers, sought refuge with the Crow near present day Lewistown. It has been said that the Nez Perce ladies, in fear for their children's lives, left them behind with the Crow so as to spare them a death by soldiers bayonet or the bitter winter cold.

Some years after Chief Joseph’s surrender at Big Hole in 1877, the Nez Perce would return to Crow Country in 1885 while on their way back to their traditional homelands in the Pacific Northwest.

The Crows also extended their invitation to the Lakota, and so it was ten years after the defeat of soldiers at Little Big Horn, Sitting Bull made plans to return to the land of his former enemies.

However, the Crow Indian Agent Henry Williamson, objected to the idea of Sitting Bull, one of the U.S. government's most bitter enemies, returning to the place he had already won a great victory only a decade earlier. Williamson voraciously sent telegrams east to the Standing Rock Agency, but no reply was ever issued.

In June 1886, fearing any outside influence and a desire of the Crows to follow the Sioux visit with a customary reciprocal visit to Sioux Country, Williamson wrote the supervisor of the Sioux chief and urged him to recall the chief back.

Yet by the time the letter got there, the Lakota chief and over 100 of his tribesmen had already set out for Crow Agency with the consent of Hunkpapa Agent James McLaughlin. Sitting Bull's band journeyed over the plains for the next few weeks, following the Missouri River back to its tributary, the Elk River, along the old route they once traversed in times of war.