Apsáalooke Artist Unveils New Work on the National Mall

By Jake Iverson / Billings Gazette

On a recent visit to Washington, D.C., Wendy Red Star was struck by how colorless the National Mall is.

“Adding some color would be an interruption to the environment and what’s happening on the Mall,” she remembered thinking.

That can be taken a few ways. For one, there’s the physical color of the memorials that dot the Mall, the vast majority of which are made of granite and marble and are still in their natural hue, a sort of milky off-white.

Wendy Red Star, an Apsáalooke artist originally from Hardin, has a new piece on the National Mall.

But there’s also the subjects of those memorials. With the notable exception of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial (another monochromatic piece of granite), nearly everything on the Mall is a monument to white men. The park at the heart of our nation’s capital only tells one type of American story, picking a few pieces out of the melting pot and leaving the rest.

Red Star is part of a group of artists who are changing that. She’s one of six artists featured in “Beyond Granite: Pulling Together,” an exhibition held on the National Mall from Aug. 18 to Sept. 18. It’s presented by the Trust for the National Mall, in partnership with the National Capital Planning Commission and the National Park Service. It’s curated by Paul Farber and Salamishah Tillet for Monument Lab, a studio in Philadelphia that bridges the gap between art and history.

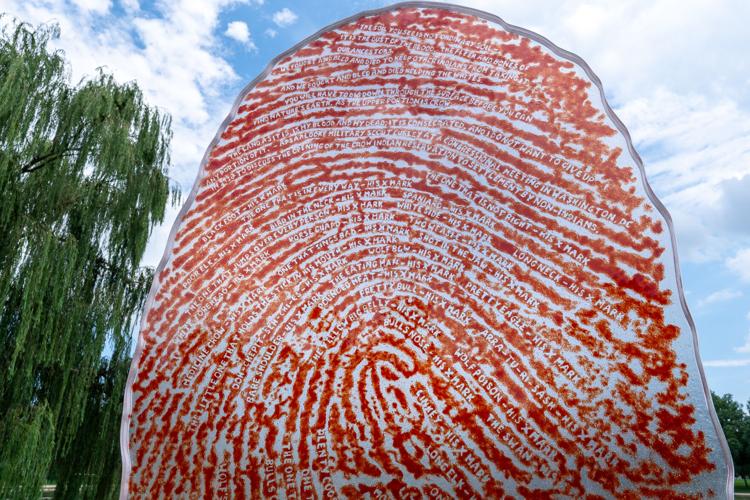

Red Star’s piece is called “The Soil You See…" Situated on the northwestern end of the Mall at Signers’ Island, which is part of Constitution Gardens. It’s a large piece of glass with a red fingerprint — Red Star’s right thumb — painted onto it.

“I can’t commit any crimes moving forward,” Red Star said and laughed.

But “The Soil You See…” is serious. It’s catching from a distance, with the mirror and paint creating a pearlescent red glow along the edge of a small pond. Viewers have to get close for “The Soil You See…” to reveal itself.

Red Star, who is a member of the Apsáalooke (Crow) tribe and was born in Billings and raised on the Crow Reservation, has filled her thumbprint’s ridges with the names of Crow leaders who signed treaties with the United States government from 1825 to 1880. She dug through digitized versions of the treaties to pull names like The Little One That Holds the Stick in his Mouth (signee of the first treaty between Americans and Crow in 1825), Shot in the Jaw (signee of the Fort Laramie treaty in 1868), Wolf Poison (signee of the unratified Fort Hawley Treaty in 1868) and familiar names like Plenty Coups and Medicine Crow (both signees of an unratified treaty in 1880).

“There’s a long history of the thumbprint being used as a way to sign federal documents,” Red Star said. Her father, who still lives on the Crow Reservation, gained a local reputation for helping fellow Crow people with their leases. He told his daughter if you look back a generation or two, you’ll find leasing documents with thumbprints in lieu of signatures. Many of the names on “The Soil You See…” are preceded by the phrase “His X mark,” meaning the signee signed with the letter X.

Just a few feet away from “The Soil You See…” sits a memorial with a very different set of signatures. It’s the memorial to the 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence, a nondescript, horseshoe-shaped granite shelf with the names and signatures of the men who signed the United States’ founding document.

Alongside quotable phrases like “All men are created equal,” the Declaration decries the “merciless Indian Savages” who lived in America. It accuses the British Crown of being unable or unwilling to protect colonialists from said “savages,” whose “known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

That phrase and charge comes from the last of the 27 “repeated injuries and usurpations” the Continental Congress used as a rationale for their declaring of independence. One of the first things America ever did was accuse Indigenous people of wanton slaughter, and asserted that only a government housed in North America could control them.

That, simply, is why “The Soil You See…” matters. It opens a dialogue about America that’s been silenced for almost 250 years.

“What’s the opposite side of the Declaration of Independence?” Red Star mused. Monument Lab first reached out to her last December, and she did a site visit in February and zeroed in on Constitution Garden.

“I wanted to be in conversation with that spot,” Red Star said.

It’s not just that one. “The Soil You See…” is within sight of the Washington Monument. From certain angles you can see the 555-foot obelisk rise behind the giant thumbprint. Long before he took the reins of the Continental Army and became the first president, Washington was nicknamed Conotocaurius — which means “Town Destroyer” — by the Iroquois people. During the Revolutionary War, Washington ordered the Sullivan Expedition, which drove into Iroquois territory and destroyed at least 40 villages. In 1790, a Seneca chief named Corn-planter told Washington that, “When your name is heard our women look behind them and turn pale, and our children cling close to the necks of their mothers.”

Red Star’s piece is also near the Lincoln Memorial. In 1862, during Lincoln’s presidency, bands of eastern Dakota or Santee Sioux people rose in armed conflict against the United States after annuity payments — which had been promised in exchange for the Dakota living on a reservation — were delayed. By the end, 358 Minnesota settlers were dead. A military trial sentenced 303 Dakota to death. President Lincoln commuted 264 of them, but still signed off on the hanging of 39 men, still the largest one-day mass execution in American history. Minnesota offered $25 per scalp of any Dakota man that was found in the state.

These are the American stories not told on the National Mall.

At least not enough. Yet. The whole exhibition was inspired by Marian Anderson, an African American opera singer who, on Easter 1939, was refused a performance at Washington’s Constitution Hall because she was Black. Without a stage, she instead performed across the street on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial where 75,000 people attended the concert, and 10-year-old Martin Luther King, Jr. listened live on the radio.

Red Star sees a connection between Washington, D.C., and the Apsáalooke people, too.

“These chiefs traveled to D.C.,” she said. “They sat with U.S. presidents. All of them interacted with the federal government to sign these treaties.”

She singled out one in particular, and wrote a quote from him at the top of “The Soil You See…” (the sculpture’s name comes from the quote.)

He is Curley, Ashishishe in Apsáalooke, a scout who served with the U.S. Army in the Sioux Wars, and is one of the only survivors from Custer’s side of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The quote Red Star picked is from a speech Curley gave in Washington during a Congressional meeting in 1912, which was a discussion about opening the Crow Reservation to non-Indian settlement.

“The soil you see is not ordinary soil,” the scout said. “It is the dust of the blood, the flesh and the bones of our ancestors… You will have to dig down through the surface before you can find nature’s earth, as the upper portion is Crow. The land as it is is my blood and my dead. It is consecrated. And I do not want to give up any portion of it.”

Those are the words visitors to the Mall are now left to mull over after they see Red Star's sculpture.

Red Star was in Washington for the opening of the exhibition, which meant she had to miss Crow Fair, the tribe’s annual celebration. She lives in Portland, Oregon, now but usually returns to Montana for the event.

Crow Fair was first established in 1904 by a U.S. Government Indian Agent as a way to ease the Crow people into the assimilation America had planned for them. But soon the tribe took control, turning the event, which was meant to focus on farming, into a celebration of all things Apsáalooke, climaxing with a series of parades and powwows and rodeos.

Red Star sees a connection between that — an act meant to nudge a group toward assimilation turned into a celebration of the culture they were meant to abandon — and the work she’s doing on the Mall.

“You talk about founding fathers, well these are my founding fathers,” she said. “It feels so good to have them acknowledged and represented.”

The exhibition will close in September, and the Mall will return to normal. But “The Soil You See…” is coming home. It will go on display at Tippet Rise, a sculpture garden in the shadow of the Beartooth Mountains near Fishtail. It’s traditional Apsáalooke land, and was ceded to the Crow people in the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. The region was removed from the reservation in 1892, as part of a proclamation by President Benjamin Harrison, which opened the land to settlement and mining.

“I’m really happy that the sculpture got this full circle thing of going to D.C., as many of the chiefs did, but then returning to Montana,” Red Star said. “It’s found its final home in Montana.”