Montana Nursing Homes Continue Closing

Residents, families stressed

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was originally published by the Daily Montanan on Nov. 20, 2022.

MISSOULA — Lonna Fox moved to Missoula in 1994 when her daughter, Sarah Koke, had her first baby, and “Grandma Lonna” has lived near her family ever since.

She helped raise her grandkids even though she’s in a wheelchair from an old spinal cord injury.

In 2013, Fox needed extra help, and she moved into Hillside Health and Rehabilitation.

But Fox is still part of the family. She has her daughter, her daughter’s husband, grandchildren and step-grandchildren in Missoula, and they go to the park and celebrate birthdays together.

This summer, Hillside announced it would close. A discharge letter said Fox, a Medicaid patient, would move to Great Falls, 165 miles and one mountain pass away.

Koke called the director of Hillside: “I said, ‘What am I going to do?’”

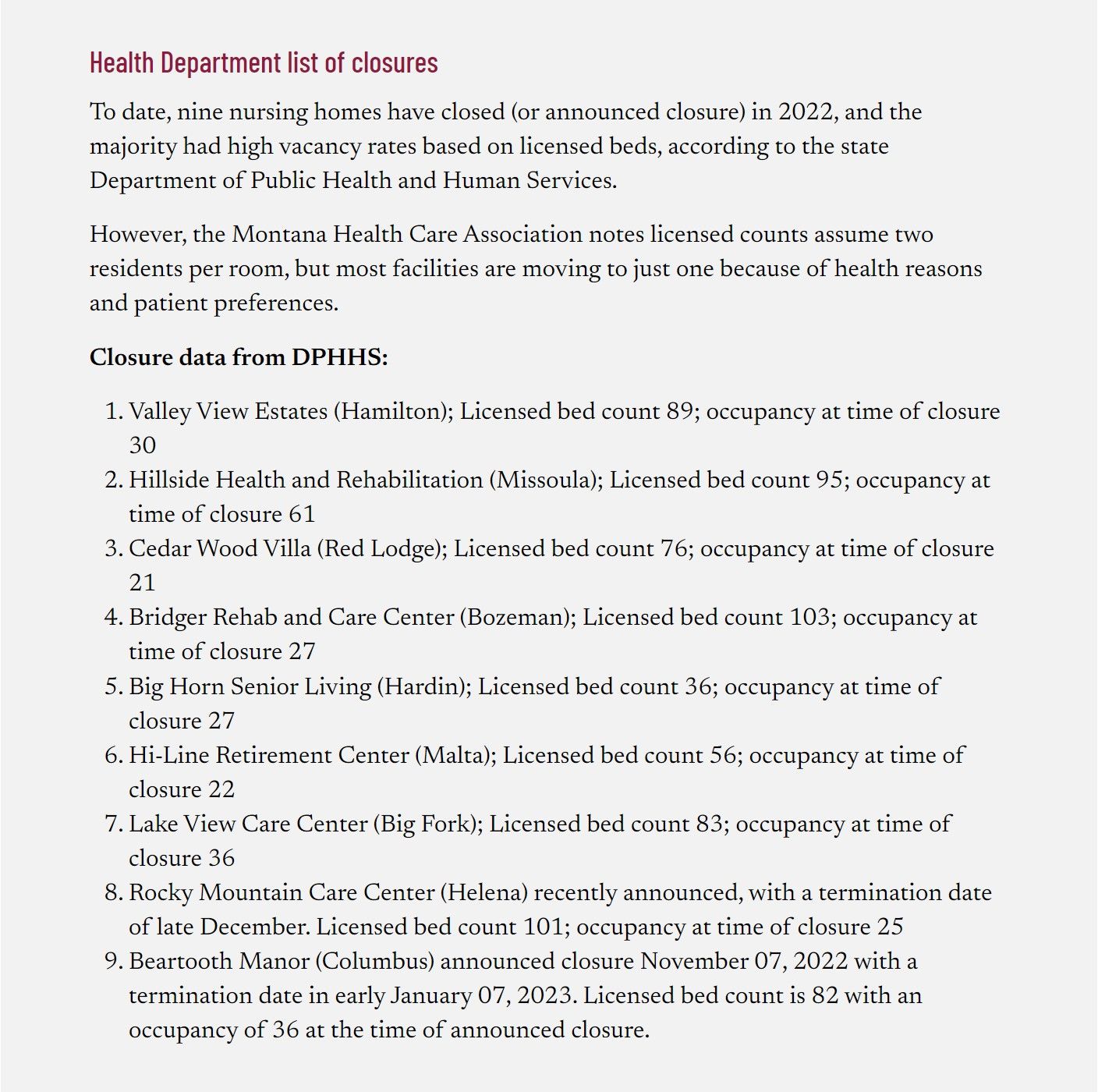

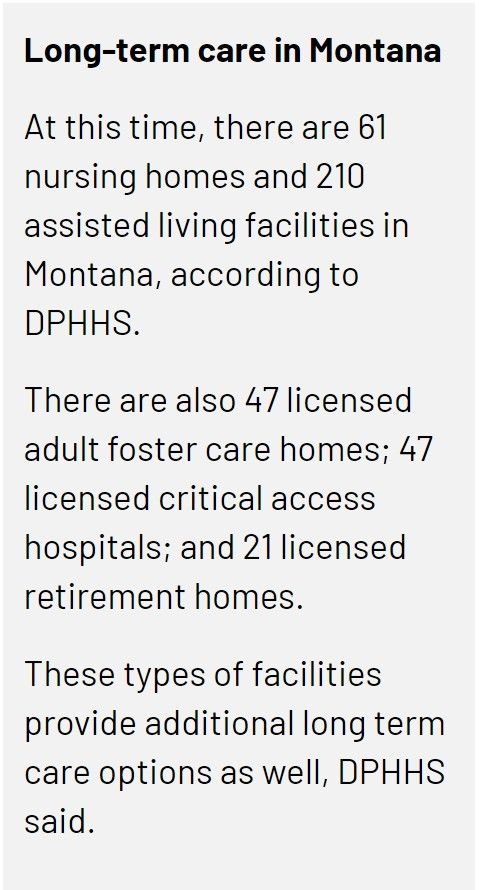

In Montana, nine nursing homes have closed or are projected to in 2022, and one transitioned from a nursing home to an assisted living facility, according to the state Department of Public Health and Human Services.

In an email, spokesperson Jon Ebelt said DPHHS did not have a projection of the number of facilities that will close in the next couple of years. However, in October, he said just 53 percent of available licensed beds were filled, and Montana has some of the lowest census rates in the country.

“This current data, as well as recent trends, suggest low demand and an overbuilt, underutilized nursing facility system in Montana,” said Ebelt, who noted the vast majority of closures included high vacancy rates.

Rose Hughes, executive director of the Montana Health Care Association, said low reimbursement rates play a large role in whether a facility can accept residents and operate.

According to the association, Medicaid accounts for 63 percent of the payment source for nursing homes. And preliminary data show nursing homes are being underpaid by more than 30 percent, said Hughes, who responded to questions via email.

The governor’s budget includes rate increases for Medicaid providers effective July 1, 2023. If the state continues to do nothing in the meantime, Hughes said, she anticipates some of the most vulnerable Montanans will be turned away from nursing homes, regardless of how they pay.

With staffing shortages and low Medicaid rates, she also anticipates more closures.

“I believe the way to avoid additional closures is to provide help as soon as possible. Facilities continue to experience losses month after month — and that is not sustainable,” Hughes said.

Fighting for Lonna Fox

When Hillside announced it would close, Koke started fighting to keep her mom in Missoula.

Fox fell off a waterfall in Provo, Utah, when she was 16 and severed her spinal cord, Koke said. She’s been in a wheelchair since, but independent.

“She’s always cared for herself, lived on her own, had her own van, her hand controls,” Koke said.

At Hillside, Koke and her family visited frequently, nearly daily, she said. During the pandemic, Koke brought Fox presents for Christmas, and Fox opened them while family members looked on from outside.

When Koke called Hillside about the closure, she said the director said her mom would be fine: “She said, ‘Don’t worry. Village has 100 rooms.’”

In Missoula, Hillside and Village Senior Residence both are managed by the Goodman Group.

So Koke called Village. She said Village told her the facility was full, but she knew that wasn’t the case.

“They ask what their insurance is,” Koke said. “If you tell them self-pay or Blue Cross or Medicare — ‘We have room.’ But Medicaid? ‘Nope. We don’t have rooms.’”

She said she knew they had space because she had called to ask if they had a short-term room available for a family member who had broken a hip and was self-pay or had Blue Cross Blue Shield.

Koke had made up the scenario to figure out if the facility was in fact full, and in that case, she said Village told her it had plenty of room.

When she said as much to Village, Koke said Village confirmed they had rooms, but only for short-term patients, and they didn’t have staff to accommodate her mom.

Abysmally low Medicaid rates are putting nursing homes out of business and shuffling frail, elderly Montanans from facility to facility and sometimes away from family and friends.– Rose Hughes, Montana Health Care Association

Koke said the Goodman Group isn’t a mom-and-pop operation. Advocating for her mom, she told them it’s a multimillion dollar company and should increase staffing and convert a room.

But workers in Montana have been hard to come by in health care and other industries.

“Bottom line is we cannot care for your mom,” Koke said she was told.

“I said, ‘You cannot, or you will not?’”

“She said, ‘Take it as you wish.’ And that ended it.”

Medicaid rates low, could go up

The Department of Public Health and Human Services said a full study of reimbursement rates is expected to be released soon.

DPHHS also said the Montana Legislature will set new rates. The legislature convenes in January, but updated rates still could be months away.

A spokesperson from the Goodman Group did not address a question asking how facilities make decisions about when to take residents given the current low reimbursement rates.

In an email, Kimberly Wild, national director of marketing, said providers need to be compensated at a rate that covers the true costs of caring for a vulnerable population.

“All communities managed by The Goodman Group in Montana accept and care for Medicaid residents,” Wild said.

But facilities such as Village have no incentive to take Medicaid patients.

Hughes said they lose at least $100 a day per patient, and 60 percent of all residents in the state are on Medicaid.

A broken model

In the meantime, Ebelt noted closures are hitting places that already don’t have a lot of residents.

For example, he said Lake View Care Center in Bigfork had a licensed bed count of 83 but just 36 residents when it closed. He said Rocky Mountain Care Center in Helena, which recently announced a termination date of late December, has 101 licensed beds, but just 25 residents.

“DPHHS is confident there is sufficient capacity to meet the skilled nursing needs of Montanans,” Ebelt said in an email.

Hughes, though, said the state’s occupancy rate is based on two patients in every room, or maximum licensed capacity. In reality, she said some facilities have converted to all private rooms, and the market trend is moving in that direction.

She said the administration has called on the industry to re-imagine the model of care, and doing so would involve converting to private rooms. Although some argue higher occupancy spreads “fixed costs” over more residents, she said the reality is facilities don’t buy food or medical supplies for people who aren’t there.

“The bottom line is that the occupancy argument simply diverts attention from what is really going on, which is that abysmally low Medicaid rates are putting nursing homes out of business and shuffling frail, elderly Montanans from facility to facility and sometimes away from family and friends,” Hughes said.

Currently, she said the main reason residents are turned away is because of insufficient staffing and the tight labor market. She said higher Medicaid rates would allow businesses to hire contract workers when necessary.

“If you are unable to admit all who seek services, you are making difficult decisions every day about which residents you are able to accept and provide care for based on all of the circumstances,” Hughes said.

A difficult resident

To try to keep her mom home, Koke called facility directors, a local nonprofit that helps seniors, corporate representatives and a state liaison. She requested a formal hearing with the health department’s Office of Administrative Hearings.

She even made thinly veiled legal threats.

“I had to come on strong,” Koke said. “I had to advocate. And the sad part is I’m pretty persistent, and I’m dedicated to my mom, and not everyone at Hillside or in these facilities has someone like that.

“And it just pulls at my heartstrings.”

Koke loves her mom, but also said she’s a difficult resident. She is in a wheelchair, has memory issues, she wears a colostomy bag needing regular changes, and needs renal stents changed or she’ll end up in the ICU.

“This is life or death stuff,” Koke said.

Fox is heavy and requires two caregivers to use a hoyer, a supportive medical device, to lift her, and not every facility has enough staff, Koke said.

She was a smoker, although she quit because some places don’t allow smokers, Koke said.

(“But she’s the nicest thing ever,” Koke said.)

The discharge letter June 22 had promised one-on-one meetings “to provide individualized assistance” and an opportunity to ask questions or express concerns about the process. But Koke said she’s the one who had to pound on the doors for information.

Then, on August 24, Fox and Koke received a letter regarding a “30 Day Notice of Transfer/Discharge.” It said Fox would be transferred in just four days — to a facility in Great Falls.

She said Hillside told her the placement was “great news.”

Koke started crying.

A challenged industry

Ebelt, with DPHHS, said facilities reserve the right to accept and deny patients based on their capacity to safely care for the resident.

“However, it is important to note that nursing homes cannot discriminate against Medicaid beneficiaries,” Ebelt said. “In addition, residents also have a right of repeal on a discharge/transfer notice.”

When facilities have closed, he said some residents have been able to stay in their communities, but some have moved on.

For example, he said residents of Bridger Rehab and Care Center in Bozeman and Hillside in Missoula generally were able to remain in their same communities because of alternate options.

He said most Big Horn Senior Living and Cedar Wood Villa residents transferred to Billings, and a couple of residents transferred out of state to be closer to family.

He also said the entire industry is changing.

For one thing, he said COVID-19 affected nursing homes and the public perception of the industry, “especially during and after shutdowns” that limited or prohibited visits. These days, people are staying at home longer.

“Currently, CMS has tasked states and the industry to reevaluate the current model of congregate living in response to the adverse COVID impacts nursing facilities in Montana and across the country experienced,” Ebelt said.

Reimbursement rates remain inadequate and out of touch with the continued rising costs of labor, supplies, services and equipment.– Kim Wild, The Goodman Group

He said CMS is working to “significantly shift” the nursing home model and (reduce beneficiary dependence) by reallocating funds to home and community-based services, HCBS: “The intent of these initiatives is to significantly lower long-term care costs, improve patient outcomes and quality of life and divert inappropriate institutionalization.”

At the same time, he said DPHHS recognizes nursing homes are part of the spectrum of care and will support them “however possible within our budget and other authorities.”

Wild, with the Goodman Group, said the entire industry is challenged.

“As with all other providers in Montana, communities managed by The Goodman Group continue to operate in an environment where reimbursement rates remain inadequate and out of touch with the continued rising costs of labor, supplies, services and equipment,” she wrote.

Staying home

Koke eventually won her fight to secure a room for her mom in Missoula.

She talked to representatives from different nursing homes, from DPHHS, and from the Goodman Group. Along the way, she was told to send her mom to Billings or Helena or Browning.

She said going out of town was not an option; she goes to doctor’s appointments with her mom and visits her and brings her home for visits too.

Once the Great Falls plan started to unravel, in part because of transportation, she said the state told her Hillside would be forced to stay open if Fox had no new home.

“Two hours later, they found her a place at Riverside,” Koke said.

Said Fox: “And here I am.”

Missoula’s Riverside is managed by the same corporation that closed Hillside, the Goodman Group. Fox said she is happier there.

“I like it better,” Fox said in an interview shortly after the move.

Koke said she’s heard Gov. Greg Gianforte argue the industry needs to change its business plan, and she understands the rationale. But she fears for other residents who don’t have family members, dogged ones, or others who can advocate as facilities close in the meantime.

“It’s only going to get worse,” Koke said.

She said their insurance shouldn’t matter, and it shouldn’t mean some residents just get “shipped off” to places that aren’t of their choosing. She believes CNAs and nurses need to be paid more too.

Fox turned to her as she was speaking: “I love you.”

“It’s amazing that we can shuffle these individuals around as if they’re a commodity,” Koke said. “These are our family. These are our loved ones. This is my mom.”